Anthropology and Ethnology During World War II

The Activity of Sektion Rassen- und Volkstumsforschung Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit in the Light of New Source Materials

Redakcja: Marcin Brocki, Małgorzata Maj, Stanisława Trebunia-Staszel

Przekład: Katarzyna Dorota Diehl

Seria: Jagiellonian Studies in Cultural Anthropology

Liczba stron: 288

Format: 15,8x23,5cm

Rok wydania: 2019

Data premiery: 25.03.2019

Data wydania e-booka: 02.06.2021

Opis książki

After reading this voluminous and, contrary to what the title might suggest, engaging study, I have no doubt that it is a great scientific achievement. Firstly, the authors managed to develop an approach to the otherwise sensitive subject of the IDO heritage that enables a cool, albeit not entirely distanced way of looking at the history of a certain institution, as well as at the entanglement of many people in its activity. The fact that the institution was established in dark times, and, in addition, by Hans Frank, should not a priori put it in the context of regular Nazi propaganda and degenerated science. The authors managed to separate what in the IDO output was based on objective research from what could never be defined as scientific. Secondly, the high level of competence of the papers in this tome makes one confident about the applied methods of presentation and interpretation of the available material, which, moreover, is still subject to further verification. This publication is not yet the final outcome of several years of research and queries, but a stop-over, an important one, on the way to further work, which is signaled throughout the book. So it is an example of work in progress.

Prof. dr hab. Wojciech Józef Burszta

Język publikacji

Angielski/English

Tłumaczenie

Katarzyna Dorota Diehl

Redakcja

Marcin Brocki

, Małgorzata Maj

, Stanisława Trebunia-Staszel

ISBN: 978-83-233-4562-6

e-ISBN (pdf): 978-83-233-9915-5

Kraj pochodzenia producenta: Polska

POLECANE KSIĄŻKI

75,00

zł

60,00

zł

NOWOŚCI

Anthropology and Ethnology During World War II

The Activity of Sektion Rassen- und Volkstumsforschung Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit in the Light of New Source Materials

RECENZJE

Reviewed by Kara Irvin (West Point)

Published on H-War (July, 2023)

Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University)

https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=58966

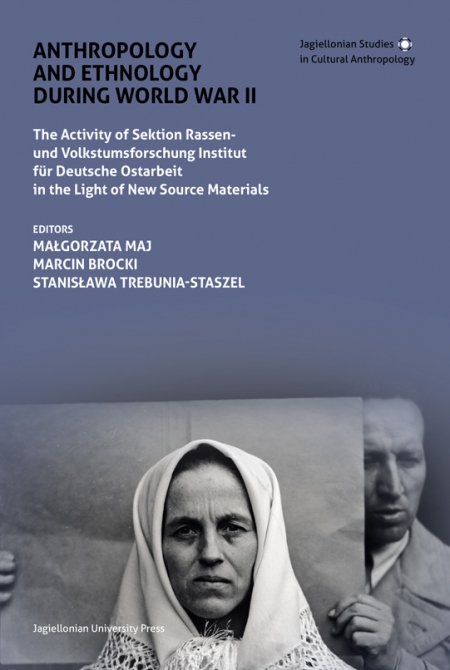

This edited volume, compiled by Polish anthropologists Małgorzata Maj, Marcin Brocki, and Stanisława Trebunia-Staszel, showcases initial research findings using the archives of the Sektion Rassen- und Volkstumsforschung (SRV). The SRV operated under the supervision of the Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit (IDO), which the editors describe as “the largest of all German institutions implementing Ostforschung and Ostpolitik in occupied Poland” (p. 7). The IDO’s staff of German anthropologists and ethnologists conducted fieldwork on behalf of the Third Reich’s political, economic, and genocidal goals. The SRV itself was further divided into three departments, each of which specialized in ethnology, anthropology, or Jewish research.

The legacy of the IDO remains complicated within present-day Poland. To be sure, many remember the German doctors and academics involved in the intrusive and (at times) terrifying collection of anthropological data. However, many others also remember the participation, and perhaps even the collaboration, of a number of professors and students who served as “Polish scientific auxiliaries.” After the war, the “auxiliaries” consistently explained that their involvement was ordered at the behest of the “authorities of the underground Polish state” in order to undermine the SRV’s goals (p. 9). A secondary line of defense indicated that Polish cooperation with the SRV presented opportunities for the “continuation of Polish science” (pp. 36-37). German evaluations of Polish staff members further complicated this dynamic, as the Polish professors, students, and clerks were described as diligent and enthusiastic.

In addition to the controversy surrounding the SRV and its Polish auxiliaries, there has also been debate within Poland regarding the SRV’s findings and whether they yielded “scientific” results. At a minimum, the editors of this volume argue that the archives of the IDO, and especially the SRV, hold legitimate historical value as “documents of war, of the life in the General Government, martyrdom and extermination, and testimonies of science at the service of a criminal state” (p. 18). This archive consists of over seventy-three thousand files including photographs, research logs, questionnaires, and psychological tests. These files were relocated from Cracow to Bavaria in 1945 and transferred to the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian two years later. In 2008, this collection was repatriated to Jagiellonian University where a team of ethnologists and anthropologists have been examining the files ever since. This edited volume represents their preliminary findings.

The volume consists of eleven chapters, with the first three serving as an extended introduction that describes the IDO, SRV, and archival documents; the way these archives returned to Jagiellonian University; and the anthropological and ethnological schools of thought in German and Polish academia in the 1930s and 1940s. Chapters 4 through 7 build on these themes by analyzing anthropological, medical, and psychological research conducted by the IDO in multiple regions of occupied Poland. In chapter 5, Krzysztof Kaczanowski analyzes the findings of a study supervised by Anton Adolf Plügel, who served as both the director of the SRV’s ethnographic section and the deputy head of the SRV between 1941 and 1942. Kaczanowski argues that the findings conform to both contemporary and current anthropological standards; however, he explicitly states that this data was obtained and interpreted for nefarious purposes. Chapter 5 by Lisa Gottschall provides a short intellectual biography of Plügel, describing his childhood and university education in Austria as well as an overview of his time in occupied Poland. Chapter 6, written by Maj and Trebunia-Staszel, and chapter 7, written by Jan Święch, examine the reports of the ethnographic department under Plügel and his successors and illustrate how their research nested with plans for exhibits at regional museums sponsored by the General Government. In chapter 9, Jacek Tejchma describes his brief correspondence with Gisela (Hildebrandt) Pietsch, one of Plügel’s successors, to learn more about the history of his village, Markowa, during the German occupation. Chapters 8, 10, and 11 are perhaps the most interesting as they examine the SRV’s photographic archive, describe recent interviews with the then-children who were subjects of these anthropological studies, and consider additional opportunities for research.

This volume will be of immense interest to anyone studying Polish or German history during the years of occupation, particularly because it previews the rich archival materials available for research. The translation in many areas is awkward, but this should not deter English-speaking historians or anthropologists from consulting this work. Perhaps the volume’s greatest strength lies in the editors’ decision to publish numerous photos and documents after each chapter. This structure allows readers to “visit” the archive and preview the types of artifacts the SRV left behind. Even more important, these published photographs remind us that the subjects of these studies were real men, women, and children studied with the purpose of determining their racial “value” and—at least in the case of the children—whether or not they could be “germanized.” Looking at the photos of these adults and children, one wonders what happened to them during and after the war. Were they allowed to remain in their villages in peace? Were some deported as forced laborers or candidates for “germanization”? We may never learn of their fates, but Maj and her research team have taken a significant first step by reminding us that the victims of German racial policies—whether targeted for extermination, assimilation, or otherwise—were more than just names on a list but real people with lives worth remembering.

Published on H-War (July, 2023)

Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University)

https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=58966

This edited volume, compiled by Polish anthropologists Małgorzata Maj, Marcin Brocki, and Stanisława Trebunia-Staszel, showcases initial research findings using the archives of the Sektion Rassen- und Volkstumsforschung (SRV). The SRV operated under the supervision of the Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit (IDO), which the editors describe as “the largest of all German institutions implementing Ostforschung and Ostpolitik in occupied Poland” (p. 7). The IDO’s staff of German anthropologists and ethnologists conducted fieldwork on behalf of the Third Reich’s political, economic, and genocidal goals. The SRV itself was further divided into three departments, each of which specialized in ethnology, anthropology, or Jewish research.

The legacy of the IDO remains complicated within present-day Poland. To be sure, many remember the German doctors and academics involved in the intrusive and (at times) terrifying collection of anthropological data. However, many others also remember the participation, and perhaps even the collaboration, of a number of professors and students who served as “Polish scientific auxiliaries.” After the war, the “auxiliaries” consistently explained that their involvement was ordered at the behest of the “authorities of the underground Polish state” in order to undermine the SRV’s goals (p. 9). A secondary line of defense indicated that Polish cooperation with the SRV presented opportunities for the “continuation of Polish science” (pp. 36-37). German evaluations of Polish staff members further complicated this dynamic, as the Polish professors, students, and clerks were described as diligent and enthusiastic.

In addition to the controversy surrounding the SRV and its Polish auxiliaries, there has also been debate within Poland regarding the SRV’s findings and whether they yielded “scientific” results. At a minimum, the editors of this volume argue that the archives of the IDO, and especially the SRV, hold legitimate historical value as “documents of war, of the life in the General Government, martyrdom and extermination, and testimonies of science at the service of a criminal state” (p. 18). This archive consists of over seventy-three thousand files including photographs, research logs, questionnaires, and psychological tests. These files were relocated from Cracow to Bavaria in 1945 and transferred to the National Anthropological Archives at the Smithsonian two years later. In 2008, this collection was repatriated to Jagiellonian University where a team of ethnologists and anthropologists have been examining the files ever since. This edited volume represents their preliminary findings.

The volume consists of eleven chapters, with the first three serving as an extended introduction that describes the IDO, SRV, and archival documents; the way these archives returned to Jagiellonian University; and the anthropological and ethnological schools of thought in German and Polish academia in the 1930s and 1940s. Chapters 4 through 7 build on these themes by analyzing anthropological, medical, and psychological research conducted by the IDO in multiple regions of occupied Poland. In chapter 5, Krzysztof Kaczanowski analyzes the findings of a study supervised by Anton Adolf Plügel, who served as both the director of the SRV’s ethnographic section and the deputy head of the SRV between 1941 and 1942. Kaczanowski argues that the findings conform to both contemporary and current anthropological standards; however, he explicitly states that this data was obtained and interpreted for nefarious purposes. Chapter 5 by Lisa Gottschall provides a short intellectual biography of Plügel, describing his childhood and university education in Austria as well as an overview of his time in occupied Poland. Chapter 6, written by Maj and Trebunia-Staszel, and chapter 7, written by Jan Święch, examine the reports of the ethnographic department under Plügel and his successors and illustrate how their research nested with plans for exhibits at regional museums sponsored by the General Government. In chapter 9, Jacek Tejchma describes his brief correspondence with Gisela (Hildebrandt) Pietsch, one of Plügel’s successors, to learn more about the history of his village, Markowa, during the German occupation. Chapters 8, 10, and 11 are perhaps the most interesting as they examine the SRV’s photographic archive, describe recent interviews with the then-children who were subjects of these anthropological studies, and consider additional opportunities for research.

This volume will be of immense interest to anyone studying Polish or German history during the years of occupation, particularly because it previews the rich archival materials available for research. The translation in many areas is awkward, but this should not deter English-speaking historians or anthropologists from consulting this work. Perhaps the volume’s greatest strength lies in the editors’ decision to publish numerous photos and documents after each chapter. This structure allows readers to “visit” the archive and preview the types of artifacts the SRV left behind. Even more important, these published photographs remind us that the subjects of these studies were real men, women, and children studied with the purpose of determining their racial “value” and—at least in the case of the children—whether or not they could be “germanized.” Looking at the photos of these adults and children, one wonders what happened to them during and after the war. Were they allowed to remain in their villages in peace? Were some deported as forced laborers or candidates for “germanization”? We may never learn of their fates, but Maj and her research team have taken a significant first step by reminding us that the victims of German racial policies—whether targeted for extermination, assimilation, or otherwise—were more than just names on a list but real people with lives worth remembering.

Anthropology and Ethnology During World War II

The Activity of Sektion Rassen- und Volkstumsforschung Institut für Deutsche Ostarbeit in the Light of New Source Materials

Wybierz rozdziały:

Wartość zamówienia:

0.00 zł